OSPF Features

OSPF Hierarchy

configuring and Verifying OSPF

OSPF Details

Link State Protocol

100% loop free topology

Fast convergence

Classless routing - understands variable length subnet mask (VLSM)

Use Cost (Bandwidth) as Metric

Sends Partial updates only LSA - only when network change

Administrative Distance is 110

router(config)# router ospf <process-id> - internal number on router

router(config-router)# network <network> <wildcard-mask> area <area-id> - start helo packets

Example

routerA(config)# router ospf 5

routerA(config-router)# network 192.168.1.0 0.0.0.0.5 area 0

routerA(config-router)# network 12.12.12.0 0.0.0.0.5 area 0

routerA(config-router)# network 13.13.13.0 0.0.0.0.5 area 0

OSPF configuration

routerA Fe0/1 192.168.1.1/24, S0/0/0 12.12.12.1/24, S0/0/1 12.12.12.1/24

routerB Fe0/1 192.168.2.1/24, S0/0/0 12.12.12.2/24, S0/0/1 13.13.13.1/24

routerc Fe0/1 192.168.3.1/24, S0/0/0 12.12.12.2/24, S0/0/1 13.13.13.1/24

OSPF Configuration Verification

routerA# show ip protocols (displays info about all routing protocols running on the router)

routerA# show ip route (displays the routing table of the router)

routerA# show ip ospf neighbor (displays the OSPF neighbor Table)

routerA# show running-config (Displays the Routers running configurations)

Redistribute a static or directly connect routes into OSPF

MUST follow this order

1. create prefix list

2. create router map

3. create ospf redistribution

see example in router

Step 1

ip prefix-list connected_into_ospf seq 5 permit 10.85.246.2/32 (prefix listed for the router map)

!

ip prefix-list static_into_ospf seq 5 permit 10.85.246.128/25

Step 2

!

route-map connected_into_opsf permit 10

match ip address prefix-list connected_into_opsf

set tag 1002

!

Step 3

router ospf 3768

log-adjacency-changes

area 853 authentication message-digest

redistribute connected metric-type 1 subnets route-map connected_into_opsf

redistribute static metric 1 subnets route-map static_into_ospf

passive-interface Loopback0

network 10.85.246.12 0.0.0.3 area 853

Over three decades of Information Technology experience, specializing in High Performance Networks, Security Architecture, E-Commerce Engineering, Data Center Design, Implementation and Support

Saturday, November 5, 2016

Friday, October 21, 2016

Firewall Policy Rules Basics

Policy via Check Point SmartDashboard

Basic

Rules

There are two basic rules used by nearly all

Security Gateway Administrators: the Cleanup Rule and the Stealth Rule. Both

the Cleanup and Stealth Rules are important for creating basic security

measures, and tracking important information in SmartView Tracker.

Cleanup Rule - The Security Gateway follows the principle, "That

which is not expressly permitted is prohibited." Security Gateway drop all

communication attempts that do not match a rule. The only way to monitor the

dropped packets is to create a Cleanup Rule that logs all dropped traffic. The

Cleanup Rule, also known as the "None of the Above" rule, drops all

communication not described by any other rules, and allows you to specify

logging for everything being dropped by this rule.

Stealth Rule - To prevent any users from connecting directly to the

Gateway, you should add a Stealth Rule to your Rule Base. Protecting the

Gateway in this manner makes the Gateway transparent to the network. The

Gateway becomes invisible to users on the network.

In most cases, the Stealth Rule should be

placed above all other rules. Placing the Stealth Rule at the top of the Rule

Base protects your Gateway from port scanning, spoofing, and other types of

direct attacks. Connections that need to be made directly to the Gateway, such

as Client Authentication, encryption and Content Vectoring Protocol (CVP)

rules, always go above the Stealth Rule.

Implicit/Explicit Rules

The Security Gateway creates a Rule Base by

translating the Security Policy into a collection of individual rules. The

Security Gateway creates implicit rules, derived from Gloabl Properties and

explicit rules, created by the Administrator in the SmartDashboard.

An explicit

rule is a rule that you create in the Rule Base. Explicit rules are displayed

together with implicit rules in the correct sequence, when you select to view

implies rules. To see how properties and rules interact, select Implied Rules

from the view menu. Implicit rules appear without numbering, and explicit rules

appear with numbering.

Implicit rules are defined by

the Security Gateway to allow certain connections to and from the Gateway, with

a variety of different services. The Gateway enforces two types of implicit

rules that enable the following:

* Control Connections

* Outgoing packets

Rule Base Management

As a network infrastructure grows, so will the

Rule Base created to manage the network's traffic. If not managed properly,

Rule Base order can affect Security Gateway performance and negatively impact

traffic on the protected networks. Here are some general guidelines to help you

manage your Rule Base effectively.

Before creating a Rule Base for your system,

answer the following questions:

1. Which objects are in the network? Examples

include gateways, hosts, networks, routers, and domains.

2. Which user permissions and authentication

schemes are needed?

3. Which services, including customized

services and sessions, are allowed across the network?

As you formulate the Rule Base for your Policy, these tips

are useful to consider:

* The Policy is enforced from top to bottom.

* Place the most restrictive rules at the top of the

Policy, then proceed with the generalized rules further down the Rule Base.

If more permissive rules are located at the top, the restrictive rule may not

be used properly. This allows misuse or unintended use of access, or an

intrusion, due to improper rule configuration.

* Keep it simple. Grouping objects or combining rules makes for visual clarity and

simplifies debugging. If more than 50 rules are used, the Security Policy

becomes hard to manage. Security Administrators may have difficulty determining

how rules interact.

* Add a Stealth

Rule and Cleanup Rule first to each new Policy Package. A Stealth Rule

blocks access to the Gateway. Using an Explicit Drop Rule is recommended for

logging purposes.

* Limit the use of the Reject action in rules. If a rule is configured to reject, a

message is returned to the source address, informing that the connection is not

permitted.

* Use section

titles to group similar rules according to their function. For example,

rules controlling access to a DMZ should be placed together. Rules allowing an

internal network access to the Internet should be placed together and so on.

This allows easier modification of the Rule Base, as it is easier to locate the

appropriate rules.

* Comment

each rule! Documentation eases troubleshooting, and explains why rules

exist. This assist when reviewing the Security Policy for errors and

modifications. This is particularly important when the Policy is managed by

multiple Administrators. In addition, this Comment option is available when

saving database version. See the Database Revision Control section in this

chapter.

* For efficiency, the most frequently used

rules are placed above less-frequently used rules. This must be done carefully,

to ensure a general-accept rule is not placed before a specific-drop rule.

Under Firewall tab, there’s no policy package installed by default on the security gateway.

There are two ways to create a firewall rule: use the Add Rule at the Bottom or Add Rule at the Topicons OR click Launch Menu > Rules > Add Rule > select Bottom or Top.

Double-click on the empty Name field and give a name Allow Management Traffic for to help in troubleshooting and click OK.

You can drag and drop a Network Object under the Rule fields, such as Source, Destination, etc. OR click the plus (+) symbol, search for the Network Object or create a new Network Object by clickingNew.

Under Service, you could either click on the serving tray icon for the Service Objects OR click on the plus (+) symbol, choose either TCP or UDP (or both) and search for the specific port or service such as SSH.

Under Action, do a right-click and choose accept (permit).

You can drag the columns to display Track and under Track, do a right-click and choose Log to generate logs on SmartTracker.

Under Install On, the default behavior is to push the rules on all security gateways. Double-click and choose Targets and select the Security Gateway (in this case HQ-SG1).

Create a Stealth Rule to drop and log malicious users trying to access the Security Gateway device.

.

Create a rule to allow and log all inside users to go out to any destinations. It’s not practical to enable logging for inside users in a real environment.

Lastly, create a Cleanup rule to drop and log traffic not hitting the rules above it (implicit deny in Cisco).

You save the firewall policies either in three ways: go to Launch Menu > File > Save, do a Ctrl+S OR click on the floppy disk icon beside the Launch Menu.

You can view the Implicit Rules in either two ways: go to Launch Menu > Policy > Global PropertiesOR click Edit Global Properties using the wrench and screwdriver icon. For this lab I've enabled log traffic hitting the Implied Rule (not advisable in a production network).

To view the Implied Rules, go to Launch Menu > View > Implied Rules.

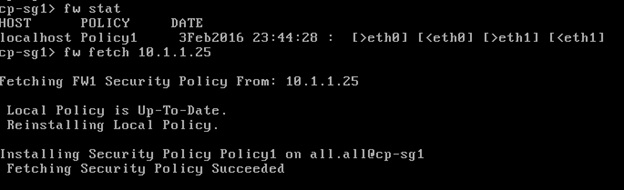

There’s an initial policy to drop ICMP on the Security Gateway. You can view the initial policy (and date/time when it was pushed) by issuing the fw stat CLI command on the Security Gateway. To remove the policy for troubleshooting purpose, we issue the fw unloadlocal command.

To revert back the initial policy, issue the fw fetch localhost command.

To save and name the policy and name it Policy-1 (no space allowed) and it will change the name from Standard to the new policy name. Then we push the policy rules by either two ways: go toLaunch Menu > Policy > Install or click on the Install Policy icon.

It will show a list of Security Gateway that you want to install our policy. Under Advance > Revision Control, we can backup by creating a database for all the objects and rules we’ve just created. This is useful when doing a rollback.

In this case I should've uncheck the Desktop Security since it will show an installation ended with an error afterwards.

Verify the new policy installed using the fw stat command. You can also install a new policy from the Security Management Server (SMS) using the fw fetch <SMS IP ADDRESS> command.

Wednesday, October 5, 2016

How TCP/IP Works

How TCP/IP Works

In this section

Ideally, TCP/IP is used whenever Windows-based computers communicate over networks.

This subject describes the components of the TCP/IP Protocol Suite, the protocol architecture, which functions TCP/IP performs, how addresses are structured and assigned, and how packets are structured and routed.

Microsoft Windows Server 2003 provides extensive support for the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) suite, as both a protocol and a set of services for connectivity and management of IP internetworks. Knowledge of the basic concepts of TCP/IP is an absolute requirement for the proper understanding of the configuration, deployment, and troubleshooting of IP-based Windows Server 2003 and Microsoft Windows 2000 intranets.

-

TCP/IP Protocol Architecture

-

IPv4 Addressing

-

Name Resolution

-

IPv4 Routing

-

Physical Address Resolution

-

Related Information

Ideally, TCP/IP is used whenever Windows-based computers communicate over networks.

This subject describes the components of the TCP/IP Protocol Suite, the protocol architecture, which functions TCP/IP performs, how addresses are structured and assigned, and how packets are structured and routed.

Microsoft Windows Server 2003 provides extensive support for the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) suite, as both a protocol and a set of services for connectivity and management of IP internetworks. Knowledge of the basic concepts of TCP/IP is an absolute requirement for the proper understanding of the configuration, deployment, and troubleshooting of IP-based Windows Server 2003 and Microsoft Windows 2000 intranets.

TCP/IP Protocol Architecture

TCP/IP protocols map to a four-layer conceptual model known

as the DARPA model, named after the U.S. government agency that

initially developed TCP/IP. The four layers of the DARPA model are:

Application, Transport, Internet, and Network Interface. Each layer in

the DARPA model corresponds to one or more layers of the seven-layer

Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model.

The following figure shows the TCP/IP protocol architecture.

TCP/IP Protocol Architecture

Note

Note

The following figure shows the TCP/IP protocol architecture.

TCP/IP Protocol Architecture

Note

Note

- The architectural diagram above corresponds to the Internet Protocol TCP/IP and does not reflect IP version 6. To see a TCP/IP architectural diagrm that includes IPv6, see How IPv6 Works in this technical reference.

Network Interface Layer

The Network Interface layer (also called the Network

Access layer) handles placing TCP/IP packets on the network medium and

receiving TCP/IP packets off the network medium. TCP/IP was designed to

be independent of the network access method, frame format, and medium.

In this way, TCP/IP can be used to connect differing network types.

These include local area network (LAN) media such as Ethernet and Token

Ring and WAN technologies such as X.25 and Frame Relay. Independence

from any specific network media allows TCP/IP to be adapted to new media

such as asynchronous transfer mode (ATM).

The Network Interface layer encompasses the Data Link and Physical layers of the OSI model. Note that the Internet layer does not take advantage of sequencing and acknowledgment services that might be present in the Network Interface layer. An unreliable Network Interface layer is assumed, and reliable communication through session establishment and the sequencing and acknowledgment of packets is the function of the Transport layer.

The Network Interface layer encompasses the Data Link and Physical layers of the OSI model. Note that the Internet layer does not take advantage of sequencing and acknowledgment services that might be present in the Network Interface layer. An unreliable Network Interface layer is assumed, and reliable communication through session establishment and the sequencing and acknowledgment of packets is the function of the Transport layer.

Internet Layer

The Internet layer handles addressing, packaging, and

routing functions. The core protocols of the Internet layer are IP, ARP,

ICMP, and IGMP.

- The Internet Protocol (IP) is a routable protocol that handles IP addressing, routing, and the fragmentation and reassembly of packets.

- The Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) handles resolution of an Internet layer address to a Network Interface layer address, such as a hardware address.

- The Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) handles providing diagnostic functions and reporting errors due to the unsuccessful delivery of IP packets.

- The Internet Group Management Protocol (IGMP) handles management of IP multicast group membership.

Transport Layer

The Transport layer (also known as the Host-to-Host

Transport layer) handles providing the Application layer with session

and datagram communication services. The core protocols of the Transport

layer are Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the User Datagram

Protocol (UDP).

- TCP provides a one-to-one, connection-oriented, reliable communications service. TCP handles the establishment of a TCP connection, the sequencing and acknowledgment of packets sent, and the recovery of packets lost during transmission.

- UDP provides a one-to-one or one-to-many, connectionless, unreliable communications service. UDP is used when the amount of data to be transferred is small (such as data that fits into a single packet), when you do not want the overhead of establishing a TCP connection, or when the applications or upper layer protocols provide reliable delivery.

Application Layer

The Application layer lets applications access the

services of the other layers and defines the protocols that applications

use to exchange data. There are many Application layer protocols and

new protocols are always being developed.

The most widely known Application layer protocols are those used for the exchange of user information:

The TCP/IP Application layer encompasses the responsibilities of the OSI Session, Presentation, and Application layers.

The most widely known Application layer protocols are those used for the exchange of user information:

- The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is used to transfer files that make up the Web pages of the World Wide Web.

- The File Transfer Protocol (FTP) is used for interactive file transfer.

- The Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) is used for the transfer of mail messages and attachments.

- Telnet, a terminal emulation protocol, is used for logging on remotely to network hosts.

- The Domain Name System (DNS) is used to resolve a host name to an IP address.

- The Routing Information Protocol (RIP) is a routing protocol that routers use to exchange routing information on an IP internetwork.

- The Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) is used between a network management console and network devices (routers, bridges, intelligent hubs) to collect and exchange network management information.

The TCP/IP Application layer encompasses the responsibilities of the OSI Session, Presentation, and Application layers.

TCP/IP Core Protocols

The TCP/IP protocol component that is installed in your

network operating system is a series of interconnected protocols called

the core protocols of TCP/IP. All other applications and other protocols

in the TCP/IP protocol suite rely on the basic services provided by the

following protocols: IP, ARP, ICMP, IGMP, TCP, and UDP.

IP

IP is a connectionless, unreliable datagram protocol

primarily responsible for addressing and routing packets between hosts.

Connectionless means that a session is not established before exchanging

data. Unreliable means that delivery is not guaranteed. IP always makes

a “best effort” attempt to deliver a packet. An IP packet might be

lost, delivered out of sequence, duplicated, or delayed. IP does not

attempt to recover from these types of errors. The acknowledgment of

packets delivered and the recovery of lost packets is the responsibility

of a higher-layer protocol, such as TCP. IP is defined in RFC 791.

An IP packet consists of an IP header and an IP payload. The following table describes the key fields in the IP header.

Key Fields in the IP Header

An IP packet consists of an IP header and an IP payload. The following table describes the key fields in the IP header.

Key Fields in the IP Header

| IP Header Field | Function |

|---|---|

| Source Address | The IP address of the original source of the IP datagram. |

| Destination Address | The IP address of the final destination of the IP datagram. |

| Identification | Used to identify a specific IP datagram and to identify all fragments of a specific IP datagram if fragmentation occurs. |

| Protocol | Informs IP at the destination host whether to pass the packet up to TCP, UDP, ICMP, or other protocols. |

| Checksum | A simple mathematical computation used to verify the bit-level integrity of the IP header. |

| Time to Live (TTL) | Designates the number of network segments on which the datagram is allowed to travel before being discarded by a router. The TTL is set by the sending host and is used to prevent packets from endlessly circulating on an IP internetwork. When forwarding an IP packet, routers are required to decrease the TTL by at least one. |

Fragmentation and reassembly

If a router receives an IP packet that is too large for

the network to which the packet is being forwarded, IP fragments the

original packet into smaller packets that fit on the downstream network.

When the packets arrive at their final destination, IP on the

destination host reassembles the fragments into the original payload.

This process is referred to as fragmentation and reassembly.

Fragmentation can occur in environments that have a mix of networking

media, such as Ethernet and Token Ring.

The fragmentation and reassembly works as follows:

The fragmentation and reassembly works as follows:

- When an IP packet is sent by the source, it places a unique value in the Identification field.

- The IP packet is received at the router. The IP router notes that the maximum transmission unit (MTU) of the network onto which the packet is to be forwarded is smaller than the size of the IP packet.

-

IP divides the original IP payload into fragments that fit on the next

network. Each fragment is sent with its own IP header that contains:

- The original Identification field identifying all fragments that belong together.

- The More Fragments Flag indicating that other fragments follow. The More Fragments Flag is not set on the last fragment, because no other fragments follow it.

- The Fragment Offset field indicating the position of the fragment relative to the original IP payload.

ARP

When IP packets are sent on shared access,

broadcast-based networking media — such as Ethernet or Token Ring — the

media access control (MAC) address corresponding to a forwarding IP

address must be resolved. ARP uses MAC-level broadcasts to resolve a

known forwarding or next-hop IP address to its MAC address. ARP is

defined in RFC 826.

ICMP

Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) provides

troubleshooting facilities and error reporting for packets that are

undeliverable. For example, if IP is unable to deliver a packet to the

destination host, ICMP sends a Destination Unreachable message to the

source host. The following table shows the most common ICMP messages.

Common ICMP Messages

The following table describes the most common ICMP Destination Unreachable ICMP messages.

Common ICMP Destination Unreachable Messages

ICMP does not make IP a reliable protocol. ICMP attempts

to report errors and provide feedback on specific conditions. ICMP

messages are carried as unacknowledged IP datagrams and are themselves

unreliable. ICMP is defined in RFC 792.

Common ICMP Messages

| ICMP Message | Function |

|---|---|

| Echo Request | Troubleshooting message used to check IP connectivity to a desired host. The ping utility sends ICMP Echo Request messages. |

| Echo Reply | Response to an ICMP Echo Request. |

| Redirect | Sent by a router to inform a sending host of a better route to a destination IP address. |

| Source Quench | Sent by a router to inform a sending host that its IP datagrams are being dropped due to congestion at the router. The sending host then lowers its transmission rate. Source Quench is an elective ICMP message and is not commonly implemented. |

| Destination Unreachable | Sent by a router or the destination host to inform the sending host that the datagram cannot be delivered. |

Common ICMP Destination Unreachable Messages

| Destination Unreachable Message | Description |

|---|---|

| Host Unreachable | Sent by an IP router when a route to the destination IP address cannot be found. |

| Protocol Unreachable | Sent by the destination IP node when the Protocol field in the IP header cannot be matched with an IP client protocol currently loaded. |

| Port Unreachable | Sent by the destination IP node when the Destination Port in the UDP header cannot be matched with a process using that port. |

| Fragmentation Needed and DF Set | Sent by an IP router when fragmentation must occur but is not allowed due to the source node setting the Don’t Fragment (DF) flag in the IP header. |

| Source Route Failed | Sent by an IP router when delivery of the IP packet using source route information (stored as source route option headers) fails. |

IGMP

Internet Group Management Protocol (IGMP) is a protocol

that manages host membership in IP multicast groups on a network

segment. An IP multicast group, also known as a host group, is a set of

hosts that listen for IP traffic destined for a specific IP multicast

address. IP multicast traffic is sent to a single MAC address but

processed by multiple IP hosts. A specific host listens on a specific IP

multicast address and receives all packets to that IP address.

The following are some of the additional aspects of IP multicasting:

A host supports IP multicast at one of the following levels:

IGMP messages take three forms.

The following are some of the additional aspects of IP multicasting:

- Host group membership is dynamic, hosts can join and leave the group at any time.

- A host group can be of any size.

- Members of a host group can span IP routers across multiple networks. This situation requires IP multicast support on the IP routers and the ability for hosts to register their group membership with local routers. Host registration is accomplished using IGMP.

- A host can send traffic to an IP multicast address without belonging to the corresponding host group.

A host supports IP multicast at one of the following levels:

- Level 0: No support to send or receive IP multicast traffic.

- Level 1: Support exists to send but not receive IP multicast traffic.

- Level 2: Support exists to both send and receive IP multicast traffic. Windows Server 2003, Windows 2000, Microsoft Windows NT version 3.5 and later, and TCP/IP support level 2 IP multicasting.

IGMP messages take three forms.

- Host Membership Report. When a host joins a host group, it sends an IGMP Host Membership Report message to the all-hosts IP multicast address (224.0.0.1) or to the specified IP multicast address declaring its membership in a specific host group by referencing the IP multicast address. A host can also specify the specific sources from which multicast traffic is needed.

- Host Membership Query. When a router polls a network to ensure that there are members of a specific host group, it sends an IGMP Host Membership Query message to the all-hosts IP multicast address. If no responses to the poll are received after several polls, the router assumes no membership in that group for that network and stops advertising that multicast group information to other routers.

- Group Leave. When a host is no longer interested in receiving multicast traffic sent to a specific IP multicast address and it sent the last IGMP Host Membership Report message in response to an IGMP Host Membership Query, it sends an IGMP Group Leave message to the specific IP multicast address. Local routers verify that the host sending the IGMP Group Leave message is the last group member for that multicast address on that subnet. If no responses to the poll are received after several polls, the router assumes no membership in that group for that subnet and stops advertising that multicast group information to other routers.

TCP

TCP is a reliable, connection-oriented delivery service.

The data is transmitted in segments. Connection-oriented means that a

connection must be established before hosts can exchange data.

Reliability is achieved by assigning a sequence number to each segment

transmitted. An acknowledgment is used to verify that the data is

received. For each segment sent, the receiving host must return an

acknowledgment (ACK) within a specified period for bytes received. If an

ACK is not received, the data is retransmitted. TCP is defined in RFC

793.

TCP uses byte-stream communications, wherein data within the TCP segment is treated as a sequence of bytes with no record or field boundaries. The following table describes the key fields in the TCP header.

Key Fields in the TCP Header

TCP uses byte-stream communications, wherein data within the TCP segment is treated as a sequence of bytes with no record or field boundaries. The following table describes the key fields in the TCP header.

Key Fields in the TCP Header

| Field | Function |

|---|---|

| Source Port | TCP port of sending host. |

| Destination Port | TCP port of destination host. |

| Sequence Number | Sequence number of the first byte of data in the TCP segment. |

| Acknowledgment Number | Sequence number of the byte the sender expects to receive next from the other side of the connection. |

| Window | Current size of a TCP buffer on the host sending this TCP segment to store incoming segments. |

| TCP Checksum | Verifies the bit-level integrity of the TCP header and the TCP data. |

TCP ports

A TCP port provides a specific location for delivery of

TCP segments. Port numbers below 1024 are well-known ports and are

assigned by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA). The

following table lists a few well-known TCP ports.

Well-Known TCP Ports

Well-Known TCP Ports

| TCP Port Number | Description |

|---|---|

| 20 | FTP (Data Channel) |

| 21 | FTP (Control Channel) |

| 23 | Telnet |

| 80 | HTTP used for the World Wide Web |

| 139 | NetBIOS session service |

TCP three-way handshake

A TCP connection is initialized through a three-way

handshake. The purpose of the three-way handshake is to synchronize the

sequence number and acknowledgment numbers of both sides of the

connection and exchange TCP window sizes or the use of large window

sizes or TCP timestamps. The following steps outline the process:

- The initiator of the TCP connection, typically a client, sends a TCP segment to the server with an initial Sequence Number for the connection and a window size indicating the size of a buffer on the client to store incoming segments from the server.

- The responder of the TCP connection, typically a server, sends back a TCP segment containing its chosen initial Sequence Number, an acknowledgment of the client’s Sequence Number, and a window size indicating the size of a buffer on the server to store incoming segments from the client.

- The initiator sends a TCP segment to the server containing an acknowledgment of the server’s Sequence Number.

UDP

UDP provides a connectionless datagram service that

offers unreliable, best-effort delivery of data transmitted in messages.

This means that neither the arrival of datagrams nor the correct

sequencing of delivered packets is guaranteed. UDP does not recover from

lost data through retransmission. UDP is defined in RFC 768.

UDP is used by applications that do not require an acknowledgment of receipt of data and that typically transmit small amounts of data at one time. NetBIOS name service, NetBIOS datagram service, and SNMP are examples of services and applications that use UDP. The following table describes the key fields in the UDP header.

Key Fields in the UDP Header

UDP is used by applications that do not require an acknowledgment of receipt of data and that typically transmit small amounts of data at one time. NetBIOS name service, NetBIOS datagram service, and SNMP are examples of services and applications that use UDP. The following table describes the key fields in the UDP header.

Key Fields in the UDP Header

| Field | Function |

|---|---|

| Source Port | UDP port of sending host. |

| Destination Port | UDP port of destination host. |

| UDP Checksum | Verifies the bit-level integrity of the UDP header and the UDP data. |

UDP ports

To use UDP, an application must supply the IP address

and UDP port number of the destination application. A port provides a

location for sending messages. A port functions as a multiplexed message

queue, meaning that it can receive multiple messages at a time. Each

port is identified by a unique number. It is important to note that UDP

ports are distinct and separate from TCP ports even though some of them

use the same number. The following table lists a few well-known UDP

ports.

Well-Known UDP Ports

Well-Known UDP Ports

| UDP Port Number | Description |

|---|---|

| 53 | Domain Name System (DNS) name queries |

| 69 | Trivial File Transfer Protocol (TFTP) |

| 137 | NetBIOS name service |

| 138 | NetBIOS datagram service |

| 161 | SNMP |

TCP/IP Application Interfaces

For applications to access the services offered by the core

TCP/IP protocols in a standard way, network operating systems like

Windows Server 2003 make industry-standard application programming

interfaces (APIs) available. APIs are sets of functions and commands

that are programmatically called by application code to perform network

functions. For example, a Web browser application connecting to a Web

site needs access to TCP’s connection establishment service.

The following figure shows two common TCP/IP APIs, Windows Sockets and NetBIOS, and their relation to the core protocols.

APIs for TCP/IP

The following figure shows two common TCP/IP APIs, Windows Sockets and NetBIOS, and their relation to the core protocols.

APIs for TCP/IP

Windows Sockets Interface

The Windows Sockets API is a standard API under

Windows Server 2003 for applications that use TCP and UDP. Applications

written to the Windows Sockets API run on many versions of TCP/IP.

TCP/IP utilities and the SNMP service are examples of applications

written to the Windows Sockets interface.

Windows Sockets provides services that allow applications to bind to a particular port and IP address on a host, initiate and accept a connection, send and receive data, and close a connection. There are two types of sockets:

To communicate, an application specifies the protocol, the IP address of the destination host, and the port of the destination application. After the application is connected, information can be sent and received.

Windows Sockets provides services that allow applications to bind to a particular port and IP address on a host, initiate and accept a connection, send and receive data, and close a connection. There are two types of sockets:

- A stream socket provides a two-way, reliable, sequenced, and unduplicated flow of data using TCP.

- A datagram socket provides a one-way or two-way flow of data using UDP.

To communicate, an application specifies the protocol, the IP address of the destination host, and the port of the destination application. After the application is connected, information can be sent and received.

NetBIOS Interface

NetBIOS allows applications to communicate over a

network. NetBIOS defines two entities, a session-level interfaceand a

session management and data transport protocol.

The NetBIOS interface is a standard API for user applications to submit network input/output (I/O) and control directives to underlying network protocol software. An application program that uses the NetBIOS interface API for network communication can be run on any protocol software that supports the NetBIOS interface.

NetBIOS also defines a protocolthat functions at thesession/transport level. This is implemented by the underlying protocol software (such as the NetBIOS Frames Protocol NBFP — a component of NetBEUI or NetBIOS over TCP/IP (NetBT)), which performs the network I/O required to accommodate the NetBIOS interface command set. NetBIOS over TCP/IP is defined in RFCs 1001 and 1002. NetBT is enabled by default, however Windows Server 2003 allows you to disable NetBT for an environment that contains no NetBIOS-based network clients or applications.

NetBIOS provides commands and support for NetBIOS Name Management, NetBIOS Datagrams, and NetBIOS Sessions.

The NetBIOS interface is a standard API for user applications to submit network input/output (I/O) and control directives to underlying network protocol software. An application program that uses the NetBIOS interface API for network communication can be run on any protocol software that supports the NetBIOS interface.

NetBIOS also defines a protocolthat functions at thesession/transport level. This is implemented by the underlying protocol software (such as the NetBIOS Frames Protocol NBFP — a component of NetBEUI or NetBIOS over TCP/IP (NetBT)), which performs the network I/O required to accommodate the NetBIOS interface command set. NetBIOS over TCP/IP is defined in RFCs 1001 and 1002. NetBT is enabled by default, however Windows Server 2003 allows you to disable NetBT for an environment that contains no NetBIOS-based network clients or applications.

NetBIOS provides commands and support for NetBIOS Name Management, NetBIOS Datagrams, and NetBIOS Sessions.

NetBIOS name management

NetBIOS name management services provide the following functions:

- Name registration and release. When a TCP/IP host initializes, it registers its NetBIOS names by broadcasting or directing a NetBIOS name registration request to a NetBIOS Name Server such as a WINS server. If another host has registered the same NetBIOS name, either the host or a NetBIOS Name Server responds with a negative name registration response. The initiating host receives an initialization error as a result. When the workstation service on a host is stopped, the host discontinues broadcasting a negative name registration response when someone else tries to use the name and sends a name release to a NetBIOS Name Server. The NetBIOS name is said to be released and available for use by another host.

- Name Resolution. When a NetBIOS application wants to communicate with another NetBIOS application, the IP address of the NetBIOS application must be resolved. NetBT performs this function by either broadcasting a NetBIOS name query on the local network or sending a NetBIOS name query to a NetBIOS Name Server.

NetBIOS datagrams

The NetBIOS datagram service provides delivery of

datagrams that are connectionless, unsequenced, and unreliable.

Datagrams can be directed to a specific NetBIOS name or broadcast to a

group of names. Delivery is unreliable in that only the users who are

logged on to the network receive the message. The datagram service can

initiate and receive both broadcast and directed messages. The NetBIOS

datagram service uses UDP port 138.

NetBIOS sessions

The NetBIOS session service provides delivery of

NetBIOS messages that are connection-oriented, sequenced, and reliable.

NetBIOS sessions use TCP connections and provide session establishment,

keepalive, and termination. The NetBIOS session service allows

concurrent data transfers in both directions using TCP port 139.

IPv4 Addressing

For IP version 4, each TCP/IP host is identified by a logical

IP address. The IP address is a Network layer address and has no

dependence on the Data-Link layer address (such as a MAC address of a

network adapter). A unique IP address is required for each host and

network component that communicates using TCP/IP and can be assigned

manually or by using Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP).

The IP address identifies a system’s location on the network in the same way a street address identifies a house on a city block. Just as a street address must identify a unique residence, an IP address must be globally unique to the internetwork and have a uniform format.

Each IP address includes a network ID and a host ID.

The IP address identifies a system’s location on the network in the same way a street address identifies a house on a city block. Just as a street address must identify a unique residence, an IP address must be globally unique to the internetwork and have a uniform format.

Each IP address includes a network ID and a host ID.

- The network ID (also known as a network address) identifies the systems that are located on the same physical network bounded by IP routers. All systems on the same physical network must have the same network ID. The network ID must be unique to the internetwork.

- The host ID (also known as a host address) identifies a workstation, server, router, or other TCP/IP host within a network. The host address must be unique to the network ID.

IPv4 Address Syntax

An IP address consists of 32 bits. Instead of expressing IPv4 addresses 32 bits at a time using binary notation (Base2), it is standard practice to segment the 32 bits of an IPv4 address into four 8-bit fields called octets. Each octet is converted to a decimal number (base 10) from 0–255 and separated by a period (a dot). This format is called dotted decimal notation. The following table provides an example of an IP address in binary and dotted decimal formats.

An IP Address in Binary and Dotted Decimal Formats

For example, the IPv4 address of 11000000101010000000001100011000 is:

IP Address

An IP Address in Binary and Dotted Decimal Formats

| Binary Format | Dotted Decimal Notation |

|---|---|

11000000 10101000 00000011 00011000

|

192.168.3.24

|

- Segmented into 8-bit blocks: 11000000 10101000 00000011 00011000.

- Each block is converted to decimal: 192 168 3 24

- The adjacent octets are separated by a period: 192.168.3.24.

IP Address

Types of IPv4 Addresses

The Internet standards define the following types of IPv4 addresses:

- Unicast. Assigned to a single network interface located on a specific subnet on the network and used for one-to-one communications.

- Multicast. Assigned to one or more network interfaces located on various subnets on the network and used for one-to-many communications.

- Broadcast. Assigned to all network interfaces located on a subnet on the network and used for one-to-everyone-on-a-subnet communications.

IPv4 Unicast Addresses

The IPv4 unicast address identifies an interface’s

location on the network in the same way a street address identifies a

house on a city block. Just as a street address must identify a unique

residence, an IPv4 unicast address must be globally unique to the

network and have a uniform format.

Each IPv4 unicast address includes a network ID and a host ID.

Each IPv4 unicast address includes a network ID and a host ID.

- The network ID (also known as a network address) is the fixed portion of an IPv4 unicast address that identifies the set of interfaces that are located on the same physical or logical network segment as bounded by IPv4 routers. A network segment on TCP/IP networks is also known as a subnet. All systems on the same physical or logical subnet must use the same network ID and the network ID must be unique to the entire TCP/IP network.

- The host ID (also known as a host address) is the variable portion of an IPv4 unicast address that is used to identify a network node’s interface on a subnet. The host ID must be unique to the network ID.

IPv4 Multicast Addresses

IPv4 multicast addresses are used for single-packet

one-to-many delivery. On an IPv4 multicast-enabled intranet, an IPv4

packet addressed to an IPv4 multicast address is forwarded by routers to

the subnets on which there are hosts listening to the traffic sent to

the IPv4 multicast address. IPv4 multicast provides an efficient

one-to-many delivery service for many types of communication.

IPv4 multicast addresses are defined by the class D Internet address class: 224.0.0.0/4. IPv4 multicast addresses range from 224.0.0.0 through 239.255.255.255. IPv4 multicast addresses for the 224.0.0.0/24 address prefix (224.0.0.0 through 224.0.0.255) are reserved for local subnet multicast traffic.

IPv4 multicast addresses are defined by the class D Internet address class: 224.0.0.0/4. IPv4 multicast addresses range from 224.0.0.0 through 239.255.255.255. IPv4 multicast addresses for the 224.0.0.0/24 address prefix (224.0.0.0 through 224.0.0.255) are reserved for local subnet multicast traffic.

IPv4 Broadcast Addresses

IPv4 uses a set of broadcast addresses to provide a

one-to-everyone on the subnet delivery service. Packets sent to IPv4

broadcast addresses are processed by all the interfaces on the subnet.

The following are the different types of IPv4 broadcast addresses:

- Network broadcast. Formed by setting all the host bits to 1 for a classful address prefix. An example of a network broadcast address for the classful network ID 131.107.0.0/16 is 131.107.255.255. Network broadcasts are used to send packets to all interfaces of a classful network. IPv4 routers do not forward network broadcast packets.

- Subnet broadcast. Formed by setting all the host bits to 1 for a classless address prefix. An example of a network broadcast address for the classless network ID 131.107.26.0/24 is 131.107.26.255. Subnet broadcasts are used to send packets to all hosts of a classless network. IPv4 routers do not forward subnet broadcast packets. For a classful address prefix, there is no subnet broadcast address, only a network broadcast address. For a classless address prefix, there is no network broadcast address, only a subnet broadcast address.

- All-subnets-directed broadcast. Formed by setting all the original classful network ID host bits to 1 for a classless address prefix. A packet addressed to the all-subnets-directed broadcast was defined to reach all hosts on all of the subnets of a subnetted class-based network ID. An example of an all-subnets-directed broadcast address for the subnetted network ID 131.107.26.0/24 is 131.107.255.255. The all-subnets-directed broadcast is the network broadcast address of the original classful network ID. IPv4 routers can forward all-subnets directed broadcast packets, however the use of the all-subnets-directed broadcast address is deprecated in RFC 1812.

- Limited broadcast. Formed by setting all 32 bits of the IPv4 address to 1 (255.255.255.255). The limited broadcast address is used for one-to-everyone delivery on the local subnet when the local network ID is unknown. IPv4 nodes typically only use the limited broadcast address during an automated configuration process such as Boot Protocol (BOOTP) or DHCP. For example, with DHCP, a DHCP client must use the limited broadcast address for all traffic sent until the DHCP server acknowledges the use of the offered IPv4 address configuration. IPv4 routers do not forward limited broadcast packets.

Internet Address Classes

The Internet community originally defined address classes

to accommodate different types of addresses and networks of varying

sizes. The class of address defined which bits were used for the network

ID and which bits were used for the host ID. It also defined the

possible number of networks and the number of hosts per network. Of five

address classes, class A, B, and C addresses were defined for IPv4

unicast addresses. Class D addresses were defined for IPv4 multicast

addresses and class E addresses were defined for experimental uses.

Class A

Class A network IDs were assigned to networks with a

very large number of hosts. The high-order bit in a class A address is

always set to zero, which makes the address prefix for all class A

networks and addresses 0.0.0.0/1 (or 0.0.0.0, 128.0.0.0). The next seven

bits (completing the first octet) are used to enumerate class A network

IDs. Therefore, address prefixes for class A network IDs have an 8-bit

prefix length (/8 or 255.0.0.0). The remaining 24 bits (the last three

octets) are used for the host ID. The address prefix 0.0.0.0/0 (or

0.0.0.0, 0.0.0.0) is a reserved network ID and 127.0.0.0/8 (or

127.0.0.0, 255.0.0.0) is reserved for loopback addresses. Out of a total

of 128 possible class A networks, there are 126 networks and 16,777,214

hosts per network.

Note

Structure of class A addresses

Note

- All-Zeros and All-Ones Host IDs are Reserved

- When enumerating host IDs for a given network ID, the two host IDs in which all the bits in the host ID are set to 0 (the all-zeros host ID) and all the bits in the host ID is set to 1 (the all-ones host ID) are reserved and cannot be assigned to network node interfaces. Hence, in the calculation above in which there are 24 bits for class A host IDs, the total number of possible host IDs is 16,777,216 (224). When you subtract the two reserved host IDs, the total number of usable host IDs is 16,777,214.

Structure of class A addresses

Class B

Class B network IDs were assigned to medium to

large-sized networks. The two high-order bits in a class B address are

always set to 10, which makes the address prefix for all class B

networks and addresses 128.0.0.0/2 (or 128.0.0.0, 192.0.0.0). The next

14 bits (completing the first two octets) are used to enumerate class B

network IDs. Therefore, address prefixes for class B network IDs have a

16-bit prefix length (/16 or 255.255.0.0). The remaining 16 bits (last

two octets) are used for the host ID. With 14 bits to express class B

network IDs and 16 bits to express host IDs, this allows for 16,384

networks and 65,534 hosts per network.

The following figure illustrates the structure of class B addresses.

Structure of class B addresses

The following figure illustrates the structure of class B addresses.

Structure of class B addresses

Class C

Class C addresses were assigned to small networks. The

three high-order bits in a class C address are always set to 110, which

makes the address prefix for all class C networks and addresses

192.0.0.0/3 (or 192.0.0.0, 224.0.0.0). The next 21 bits (completing the

first three octets) are used to enumerate class C network IDs.

Therefore, address prefixes for class C network IDs have a 24-bit prefix

length (/24 or 255.255.255.0). The remaining 8 bits (the last octet)

are used for the host ID. With 21 bits to express class C network IDs

and 8 bits to express host IDs, this allows for 2,097,152 networks and

254 hosts per network.

The following figure illustrates the structure of class C addresses.

Structure of class C addresses

The following figure illustrates the structure of class C addresses.

Structure of class C addresses

Class D

Class D addresses are reserved for IPv4 multicast

addresses. The four high-order bits in a class D address are always set

to 1110, which makes the address prefix for all class D addresses

224.0.0.0/4 (or 224.0.0.0, 240.0.0.0).

Class E

Class E addresses are reserved for experimental use.

The high-order bits in a class E address are set to 1111, which makes

the address prefix for all class E addresses 240.0.0.0/4 (or 240.0.0.0,

240.0.0.0)

The following table is a summary of the Internet address classes A, B, and C that can be used for IPv4 unicast addresses.

Internet Address Class Summary

The following table is a summary of the Internet address classes A, B, and C that can be used for IPv4 unicast addresses.

Internet Address Class Summary

| Class | Value for w | Network ID Portion | Host ID Portion | Network IDs | Host IDs per Network |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1-126 | w | x.y.z | 126 | 16,777,214 |

| B | 128-191 | w.x | y.z | 16,384 | 65,534 |

| C | 192-223 | w.x.y | z | 2,097,152 | 254 |

Modern Internet Addresses

The Internet address classes are an obsolete unicast

address allocation method that proved to be an inefficient way to assign

network IDs and addresses to organizations connected to the Internet.

For example, a large organization with a class A network ID can have up

to 16,777,214 hosts. However, if the organization only uses 70,000 host

IDs, then 16,707,214 potential IPv4 unicast addresses for the Internet

are wasted.

On the modern-day Internet, IPv4 address prefixes are handed out to organization’s based on the organization’s actual need for Internet-accessible IPv4 unicast addresses using a method known as Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR). For example, an organization determines that it needs 2,000 Internet-accessible IPv4 unicast addresses. The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) or an Internet service provider (ISP) allocates an IPv4 address prefix in which 21 bits are fixed, leaving 11 bits for host IDs. From the 11 bits for host IDs, the organization can create 2,032 possible IPv4 unicast addresses.

CIDR-based address allocations typically start at 8 bits. The following table lists the required number of host IDs and the corresponding prefix length for CIDR-based address allocations.

Host IDs Needed and CIDR-based Prefix Lengths

On the modern-day Internet, IPv4 address prefixes are handed out to organization’s based on the organization’s actual need for Internet-accessible IPv4 unicast addresses using a method known as Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR). For example, an organization determines that it needs 2,000 Internet-accessible IPv4 unicast addresses. The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) or an Internet service provider (ISP) allocates an IPv4 address prefix in which 21 bits are fixed, leaving 11 bits for host IDs. From the 11 bits for host IDs, the organization can create 2,032 possible IPv4 unicast addresses.

CIDR-based address allocations typically start at 8 bits. The following table lists the required number of host IDs and the corresponding prefix length for CIDR-based address allocations.

Host IDs Needed and CIDR-based Prefix Lengths

| Number of Host IDs | Prefix Length | Dotted Decimal |

|---|---|---|

| 2–254 | /24 | 255.255.255.0 |

| 255–510 | /23 | 255.255.254.0 |

| 511–1,022 | /22 | 255.255.252.0 |

| 1,021–2,046 | /21 | 255.255.248.0 |

| 2,047–4,094 | /20 | 255.255.240.0 |

| 4,095–8,190 | /19 | 255.255.224.0 |

| 8,191–16,382 | /18 | 255.255.192.0 |

| 16,383–32,766 | /17 | 255.255.128.0 |

| 32,767–65,534 | /16 | 255.255.0.0 |

Public and Private Addresses

If you want direct (routed) connectivity to the Internet,

then you must use public addresses. If you want indirect (proxied or

translated) connectivity to the Internet, you can use either public or

private addresses. If your intranet is not connected to the Internet in

any way, you can use any unicast IPv4 addresses that you want. However,

you should use private addresses to avoid network renumbering when your

intranet is eventually connected to the Internet.

Public addresses

Public addresses are assigned by ICANN and consist of

either historically allocated class-based network IDs or, more recently,

CIDR-based address prefixes that are guaranteed to be globally unique

on the Internet. For CIDR-based address prefixes, the value of w

(the first octet) is in the ranges of 1 through 126 and 128 through

223, with the exception of the private address prefixes described in

“Private Addresses.”

When the public addresses are assigned, routes are added to the routers of the Internet so that traffic sent to an address that matches the assigned public address prefix can reach the assigned organization. For example, when an organization is assigned an address prefix in the form of a network ID and prefix length, that address prefix also exists as a route in the routers of the Internet. IPv4 packets destined to an address within the assigned address prefix are routed to the proper destination.

When the public addresses are assigned, routes are added to the routers of the Internet so that traffic sent to an address that matches the assigned public address prefix can reach the assigned organization. For example, when an organization is assigned an address prefix in the form of a network ID and prefix length, that address prefix also exists as a route in the routers of the Internet. IPv4 packets destined to an address within the assigned address prefix are routed to the proper destination.

Private addresses

Each IPv4 interface requires an IPv4 address that is

globally unique to the IPv4 network. In the case of the Internet, each

IPv4 interface on a subnet connected to the Internet requires an IPv4

address that is globally unique to the Internet. As the Internet grew,

organizations connecting to the Internet required a public address for

each interface on their intranets. This requirement placed a huge demand

on the pool of available public addresses.

When analyzing the addressing needs of organizations, the designers of the Internet noted that for many organizations, most of the hosts on an organization’s intranet did not require direct connectivity to the Internet. Those hosts that did require a specific set of Internet services, such as Web access and e-mail, typically access the Internet services through Application layer gateways such as proxy servers and e-mail servers. The result is that most organizations only required a small amount of public addresses for those nodes (such as proxies, servers, routers, firewalls, and translators) that were directly connected to the Internet.

For the hosts within the organization that do not require direct access to the Internet, IPv4 addresses that do not duplicate already-assigned public addresses are required. To solve this addressing problem, the Internet designers reserved a portion of the IPv4 address space and named this space the private address space. An IPv4 address in the private address space is never assigned as a public address. IPv4 addresses within the private address space are known as private addresses. Because the public and private address spaces do not overlap, private addresses never duplicate public addresses.

The private address space specified in RFC 1918 is defined by the following address prefixes:

When analyzing the addressing needs of organizations, the designers of the Internet noted that for many organizations, most of the hosts on an organization’s intranet did not require direct connectivity to the Internet. Those hosts that did require a specific set of Internet services, such as Web access and e-mail, typically access the Internet services through Application layer gateways such as proxy servers and e-mail servers. The result is that most organizations only required a small amount of public addresses for those nodes (such as proxies, servers, routers, firewalls, and translators) that were directly connected to the Internet.

For the hosts within the organization that do not require direct access to the Internet, IPv4 addresses that do not duplicate already-assigned public addresses are required. To solve this addressing problem, the Internet designers reserved a portion of the IPv4 address space and named this space the private address space. An IPv4 address in the private address space is never assigned as a public address. IPv4 addresses within the private address space are known as private addresses. Because the public and private address spaces do not overlap, private addresses never duplicate public addresses.

The private address space specified in RFC 1918 is defined by the following address prefixes:

-

10.0.0.0/8 (10.0.0.0, 255.0.0.0)

Allows the following range of valid IPv4 unicast addresses: 10.0.0.1 to 10.255.255.254. The 10.0.0.0/8 address prefix has 24 host bits that can be used for any addressing scheme within the private organization. -

172.16.0.0/12 (172.16.0.0, 255.240.0.0)

Allows the following range of valid IPv4 unicast addresses: 172.16.0.1 to 172.31.255.254. The 172.16.0.0/12 address prefix has 20 host bits that can be used for any addressing scheme within the private organization. -

192.168.0.0/16 (192.168.0.0, 255.255.0.0)

Allows the following range of valid IPv4 unicast addresses: 192.168.0.1 to 192.168.255.254. The 192.168.0.0/16 address prefix has 16 host bits that can be used for any addressing scheme within the private organization.

Illegal addresses

Private organization intranets that do not need an

Internet connection can choose any address scheme they want, even using

public address prefixes that have been assigned by ICANN. If that

organization later decides to connect to the Internet, its current

address scheme might include addresses already assigned by ICANN to

other organizations. These addresses conflict with existing public

addresses assigned by ICANN and are known as illegal addresses.

Connectivity from illegal addresses to Internet locations is not

possible because the routers of the Internet send traffic destined to

ICANN-allocated address prefixes to the assigned organizations, not to

the organizations using illegal addresses.

For example, a private organization chooses to use the 206.73.118.0/24 address prefix for its intranet. The public address prefix 206.73.118.0/24 has been assigned by ICANN to the Microsoft Corporation and routes exist on the Internet routers to send all packets for IPv4 addresses on 206.73.118.0/24 to Microsoft routers. As long as the private organization does not connect to the Internet, there is no problem because the two address prefixes are on separate IPv4 networks; therefore they are unique to each separate network. If the private organization later connects directly to the Internet and continues to use the 206.73.118.0/24 address prefix, any Internet response traffic to locations matching the 206.73.118.0/24 address prefix is sent to Microsoft routers, not to the routers of the private organization.

For example, a private organization chooses to use the 206.73.118.0/24 address prefix for its intranet. The public address prefix 206.73.118.0/24 has been assigned by ICANN to the Microsoft Corporation and routes exist on the Internet routers to send all packets for IPv4 addresses on 206.73.118.0/24 to Microsoft routers. As long as the private organization does not connect to the Internet, there is no problem because the two address prefixes are on separate IPv4 networks; therefore they are unique to each separate network. If the private organization later connects directly to the Internet and continues to use the 206.73.118.0/24 address prefix, any Internet response traffic to locations matching the 206.73.118.0/24 address prefix is sent to Microsoft routers, not to the routers of the private organization.

Automatic Private IP Addressing

An interface on a computer running Windows Server 2003

and Windows XP that is configured to obtain an IPv4 address

configuration automatically that does not successfully contact a Dynamic

Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) server uses its alternate

configuration, as specified on the Alternate Configuration tab.

If the Automatic Private IP Address option is selected on the Alternate Configuration tab and a DHCP server cannot be found, Windows TCP/IP uses Automatic Private IP Addressing (APIPA). Windows TCP/IP randomly selects an IPv4 address from the 169.254.0.0/16 address prefix and assigns the subnet mask of 255.255.0.0. This address prefix has been reserved by the ICANN and is not reachable on the Internet. APIPA allows single-subnet Small Office/Home Office (SOHO) networks to use TCP/IP without static configuration or the administration of a DHCP server. APIPA does not configure a default gateway. Therefore, only local subnet traffic is possible.

If the Automatic Private IP Address option is selected on the Alternate Configuration tab and a DHCP server cannot be found, Windows TCP/IP uses Automatic Private IP Addressing (APIPA). Windows TCP/IP randomly selects an IPv4 address from the 169.254.0.0/16 address prefix and assigns the subnet mask of 255.255.0.0. This address prefix has been reserved by the ICANN and is not reachable on the Internet. APIPA allows single-subnet Small Office/Home Office (SOHO) networks to use TCP/IP without static configuration or the administration of a DHCP server. APIPA does not configure a default gateway. Therefore, only local subnet traffic is possible.

Special IPv4 Addresses

The following are special IPv4 addresses:

-

0.0.0.0

Known as the unspecified IPv4 address, it is used to indicate the absence of an address. The unspecified address is used only as a source address when the IPv4 node is not configured with an IPv4 address configuration and is attempting to obtain an address through a configuration protocol such as Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP). -

127.0.0.1

Known as the IPv4 loopback address, it is assigned to an internal loopback interface, enabling a node to send packets to itself.

Unicast IPv4 Addressing Guidelines

When assigning network IDs to the subnets of an organization, use the following guidelines:

-

The network ID must be unique on the IPv4 network.

If the network ID is for a subnet on which there are hosts that are directly accessible from the Internet, you must use a public IPv4 address prefix assigned by ICANN or an Internet service provider. If the network ID is for a subnet that is not directly accessible by the Internet, use either a legal public address prefix or a private address prefix that is unique on your private intranet. -

The network ID cannot begin with the numbers 0 or 127.

Both of these values for the first octet are reserved and cannot be used for IPv4 unicast addresses.

- The host ID must be unique on the subnet.

- You cannot use the all-zeros or all-ones host IDs.

- For the first IPv4 unicast address in the range, set all the host bits in the address to 0, except for the low-order bit, which is set to 1.

- For the last IPv4 unicast address in the range, set all the host bits in the address to 1, except for the low-order bit, which is set to 0.

- The first IPv4 unicast address in the range is 11000000 10101000 0001000000000001 (host bits are bold), or 192.168.16.1.

- The last IPv4 unicast address in the range is 11000000 10101000 0001111111111110 (host bits are bold), or 192.168.31.254.

Name Resolution

While IP is designed to work with the 32-bit IP addresses of

the source and the destination hosts, computers users are much better at

using and remembering names than IP addresses.

When a name is used as an alias for an IP address, a mechanism must exist for assigning that name to the appropriate IP node — to ensure its uniqueness and resolution to its IP address.

In this section, the mechanisms used for assigning and resolving host names (which are used by Windows Sockets applications), and NetBIOS names (which are used by NetBIOS applications) are discussed.

When a name is used as an alias for an IP address, a mechanism must exist for assigning that name to the appropriate IP node — to ensure its uniqueness and resolution to its IP address.

In this section, the mechanisms used for assigning and resolving host names (which are used by Windows Sockets applications), and NetBIOS names (which are used by NetBIOS applications) are discussed.

Host Name Resolution

A host name is an alias assigned to an IP node to identify

it as a TCP/IP host. The host name can be up to 255 characters long and

can contain alphabetic and numeric characters and the “-” and “.”

characters“.” Multiple host names can be assigned to the same host. For

Windows Server 2003–based computers, the host name does not have to

match the Windows Server 2003 computer name.

Windows Sockets applications, such as Microsoft Internet Explorer, can use one of two values to connect to the destination: the IP address or a host name. When the IP address is specified, name resolution is not needed. When a host name is specified, the host name must be resolved to an IP address before IP-based communication with the desired resource can begin.

Host names most commonly take the form of a domain name with a structure that follows Internet conventions. Name resolution, and domain names work the same whether they are used for IPv4 or IPv6 addresses.

Windows Sockets applications, such as Microsoft Internet Explorer, can use one of two values to connect to the destination: the IP address or a host name. When the IP address is specified, name resolution is not needed. When a host name is specified, the host name must be resolved to an IP address before IP-based communication with the desired resource can begin.

Host names most commonly take the form of a domain name with a structure that follows Internet conventions. Name resolution, and domain names work the same whether they are used for IPv4 or IPv6 addresses.

Domain Names

To meet the need for a scaleable, customizable naming

scheme for a wide variety of organizations, InterNIC has created and

maintains a hierarchical namespace called the Domain Name System (DNS).

The DNS naming scheme looks like the directory structure for files on a

disk. Usually, you trace a file path from the root directory through

subdirectories to its final location and its file name. However, a host

name is traced from its final location back through its parent domains

up to the root. The unique name of the host, representing its position

in the hierarchy, is its Fully Qualified Domain Name (FQDN). The

top-level domain namespace with second-level and subdomains is shown in

the following figure.

Domain Name System

The domain namespace includes the following categories:

The domain namespace includes the following categories:

Organizations not connected to the Internet can implement whatever top and second-level domain names they want. However, typical implementations follow InterNIC specifications so that eventual participation in the Internet will not require a renaming process.

Domain Name System

The domain namespace includes the following categories:

The domain namespace includes the following categories:- The root domain, which is indicated by “” (null), represents the root of the namespace.

- Top-level domains, directly below the root, represent types of organizations. InterNIC is responsible for the maintenance of top-level domain names on the Internet. The following table has a partial list of the Internet’s top-level domain names.

| Domain Name | Meaning |

|---|---|

| com | Commercial organization |

| edu | Educational institution |

| gov | Government institution |

| mil | Military group |

| net | Major network support center |

| org | Organization other than those above |

| int | International organization |

| <country/region code> | Each country/region (geographic scheme) |

- Second-level domains, below the top-level domains, represent specific organizations within the top-level domains. InterNIC is responsible for maintaining and ensuring uniqueness of second-level domain names on the Internet.

- Subdomains are below the second-level domain. Individual organizations are responsible for the creation and maintenance of subdomains.

- The trailing period (.) denotes that this is an FQDN with the name relative to the root of the domain namespace. The trailing period is usually not required for FQDNs and if it is missing it is assumed to be present.

- com is the top-level domain, indicating a commercial organization.

- reskit is the second-level domain, indicating the Resource Kit Corporation.

- wcoast is a subdomain of reskit.com indicating the West Coast division of the Resource Kit Corporation.

- websrv is the name of the Web server in the West Coast division.

Organizations not connected to the Internet can implement whatever top and second-level domain names they want. However, typical implementations follow InterNIC specifications so that eventual participation in the Internet will not require a renaming process.

Host Name Resolution Using a Hosts File

One common way to resolve a host name to an IP address is

to use a locally stored database file that contains

IP-address-to-host-name mappings. On most UNIX systems, this file is

/etc/hosts. On Windows Server 2003 systems, it is the Hosts file in the %systemroot%\System32\Drivers\Etc directory.

The following is an example of the contents of the Hosts file:

Within the Hosts file:

The advantage of using a Hosts file is that it is customizable for the user. Users can create whatever entries they want, including easy-to-remember nicknames for frequently accessed resources. However, the individual maintenance of the Hosts file does not scale well to storing large numbers of FQDN mappings.

The following is an example of the contents of the Hosts file:

# Table of IP addresses and host names # 127.0.0.1 localhost 131.107.34.1 router 172.30.45.121 server1.central.reskit.com s1

- Multiple host names can be assigned to the same IP address. Note that the server at the IP address 172.30.45.121 can be referred to by its FQDN (server1.central.reskit.com) or a nickname (s1). This allows the user at this computer to refer to this server using the nickname s1 instead of typing the entire FQDN.

- Entries can be case sensitive depending on the platform. Entries in the Hosts file for UNIX computers are case-sensitive. Entries in the Hosts file for Windows Server 2003, Windows XP, and Windows 2000–based computers are not case sensitive.

The advantage of using a Hosts file is that it is customizable for the user. Users can create whatever entries they want, including easy-to-remember nicknames for frequently accessed resources. However, the individual maintenance of the Hosts file does not scale well to storing large numbers of FQDN mappings.

Host Name Resolution Using a DNS Server

To make host name resolution scalable and centrally

manageable, IP address mappings for FQDNs are stored on DNS servers. To

enable the querying of a DNS server by a host computer, a component

called the DNS resolver is enabled and configured with the IP address of

the DNS server. The DNS resolver is a built-in component of TCP/IP

protocol stacks supplied with most network operating systems, including

Windows Server 2003.

When a Windows Sockets application is given an FQDN as the destination location, the application calls a Windows Sockets function to resolve the name to an IP address. The request is passed to the DNS resolver component in the TCP/IP protocol. The DNS resolver packages the FQDN request as a DNS Name Query packet and sends it to the DNS server.

DNS is a distributed naming system. Instead of storing all the records for the entire namespace on each DNS server, each DNS server stores only the records for a specific portion of the namespace. The DNS server is authoritative for the portion of the namespace that corresponds to records stored on that DNS server. In the case of the Internet, hundreds of DNS servers store various portions of the Internet namespace. To facilitate the resolution of any valid domain name by any DNS server, DNS servers are also configured with pointer records to other DNS servers.

The following process outlines what happens when the DNS resolver component on a host sends a DNS query to a DNS server. This process is shown in the following figure and is simplified so that you can gain a basic understanding of the DNS resolution process.

To obtain the IP address of a server that is

authoritative for the FQDN, DNS servers on the Internet go through an

iterative process of querying multiple DNS servers until the

authoritative server is found. For more information about DNS

name-resolution processes, see the DNS Technical Reference.

To obtain the IP address of a server that is

authoritative for the FQDN, DNS servers on the Internet go through an

iterative process of querying multiple DNS servers until the

authoritative server is found. For more information about DNS

name-resolution processes, see the DNS Technical Reference.

When a Windows Sockets application is given an FQDN as the destination location, the application calls a Windows Sockets function to resolve the name to an IP address. The request is passed to the DNS resolver component in the TCP/IP protocol. The DNS resolver packages the FQDN request as a DNS Name Query packet and sends it to the DNS server.